One of the defining contests in modern American politics, are the battles over public assistance. Underappreciated is the background noise informing opposition to income-based programs (also called means-tested programs) like Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF), Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and Section 8 housing. The way that we measure poverty (and thereby “neediness”) generates a false picture of poverty in America and income-based programs arguably exacerbate this problem by distributing resources in a manner that conservatives and liberals both find inequitable but for different reasons. Public assistance and child/family tax credits remain vulnerable because there is a dogged perception amongst conservatives, specifically, that we are helping people who do not technically need our help. Therefore, if you want to protect public assistance then you need to understand the pivotal background issue driving opposition—how we determine poverty.

This post’s history foray is more relevant than usual. When the Johnson administration was planning their Great Society initiatives, they realized that they needed to measure poverty in order to determine the scope of need, the places where need was greatest, and if their initiatives were decreasing poverty. From the bowels of the Social Security Administration, the Johnson team discovered a formula for poverty developed by economist Mollie Orshansky in the mid-1960’s. It was simple in theory and execution.

Orshansky determined that the most critical, non-negotiable need a household must meet was basic nutrition. A household that could not do so was objectively poor. Furthermore, in the early 1960’s food was a third of a family’s household budget further positioning it as the variable that mattered most. With help from the Department of Agriculture, Oshansky determined the base cost of an adequate diet. Oshansky’s formula for poverty:

Cost of an adequate diet for one adult * 3 individuals in the household

And that is the metric we use to measure poverty today, literally. It is commonly referred to as the federal poverty level and is used by the federal and state government as well as private parties (e.g. energy assistance or relief provided by utility companies) to determine income eligibility for assistance programs.

We take the rate for an adult basic diet in 1965, multiply it by ‘3’, and adjust by a percentage increase in inflation using the Consumer Price Index.

Why in heaven’s name are we using a 1965 baseline for 2025 poverty? Because changing the formula is as controversial in the halls of power as the ends to which it is used—to define eligibility for income-based programs. Adjusting the formula, depending on your method, always has a significant impact—making more or less Americans eligible for income-based assistance. And honestly, who in their right mind wants to explain formulas to their constituents?

Absolutely no one which is why we have experienced decades of arcane tinkering on the edges that makes conservatives look “mean” and liberals look “weak”.

When the Trump administration proposed in 2019 changing how the federal poverty level is adjusted annually for inflation, people lost their minds. The Office of Management & Budget fielded in excess of 5,000 official comments from leaders and social safety net providers. The initiative was abandoned. Truth be told, the Trump method for calculating annual inflation is a better method. The problem was trying to explain an economic model for inflation to the American public especially when the change would have made current recipients of income-based assistance ineligible. The enhanced accuracy of the new inflation calculation proposed by Trump could not and did not compete with the cacophony of voices who said the cost of changing the broken federal poverty level calculation was too expensive for America’s poor.

If we want to be informed participants in the battles over income-based programs, we need to take our vitamins. Let’s dig in.

There are four core criticisms of how the federal poverty level is determined:

- The calculation is based on earned income and therefore excludes cash benefits which are explicitly relevant to poor persons—e.g. Social Security for older adults, Social Security Insurance for the disabled, TANF, SNAP, and tax credits (e.g. Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit). These exclusions produce a distorted understanding of the actual cash resources that a household has at its disposal thereby overstating its poverty.

- The calculation is based on food costs because that was where one-third of 1960’s families spent their money. In 2025, food is not the primary expense households experience. The place held by food in the budgets of 1960’s families has been replaced by: housing, childcare, and healthcare. Housing, specifically, is the key driver of poverty as it consumes upwards of 35% of poor households’ budgets. Therefore, when we are determining a family’s “neediness” we are looking at the wrong variable—food—when it should be housing but ideally a more robust basket of household expenses that includes: food, housing, and healthcare.

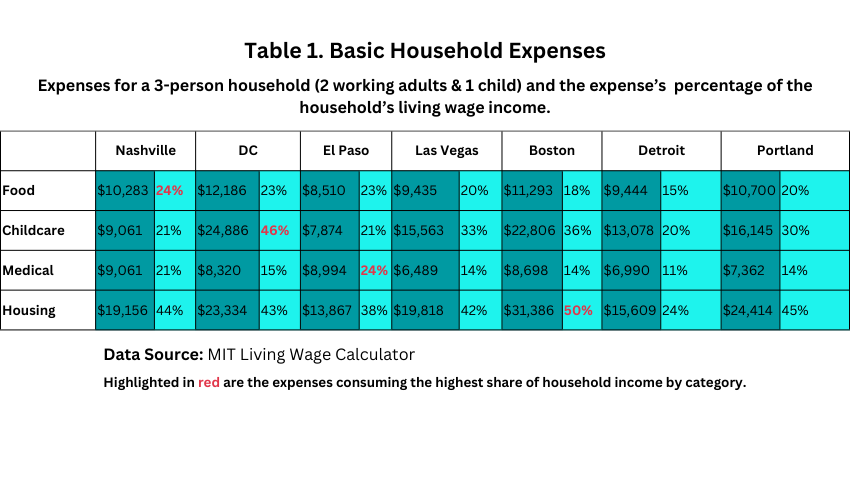

Looking at household expenses for a family of 3 in a midsize American city, their housing expenses are 20% higher than their food costs with the exception of El Paso where housing is extremely affordable.

Moreover, households in 2025 are often spending as much on food as they are spending on childcare and medical care. Food is no longer, not even close, to being the single most important expense for families, therefore, eroding confidence that the federal poverty level is an accurate indicator of poverty in America.

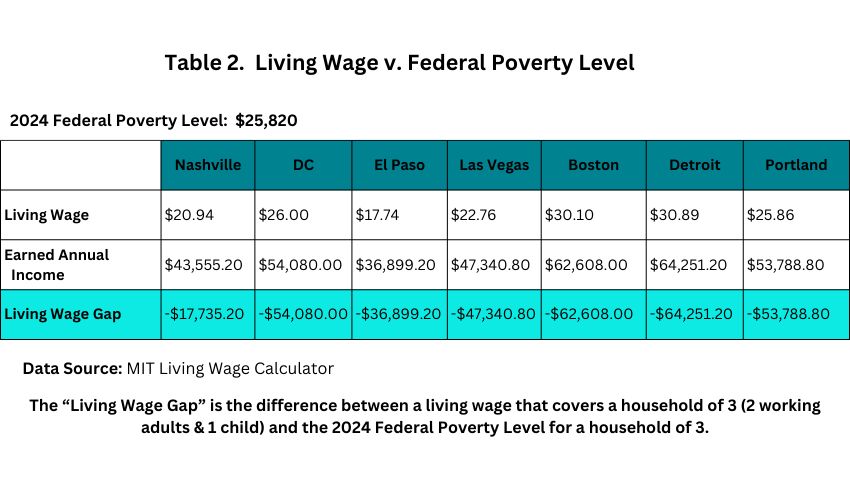

The federal poverty level is calculated for the continental United States, Alaska and Hawaii and therefore fails to reflect the significant regional variation in the cost of living and inflation. MIT’s living wage calculations reveal how dramatic the actual cost of living is around the United States. For example, if we look at the living wage estimates for 7 midsize cities, we find that bridging the poverty gap is a dramatically steeper climb for families in Detroit than El Paso.

- The current use of the Consumer Price Index for Urban Workers (CPI-U) to calculate annual inflation adjustments overestimates the impact of inflation on households. This is the battle that the Trump administration took on. The easiest way to explain why the CPI-U is problematic is to understand how consumers behave. When there is inflation, consumers, especially the poor, do not continue buying price inflated goods if there is a cheaper alternative or they may simply go without. Imagine if the cost of beef went through the roof. Most Americans would switch to a less costly alternative like chicken or pork. They would not continue purchasing the inflated beef products. As a result, their exposure to inflation is mitigated. The CPI-U does not take this consumer behavior into consideration and as a result assumes everyone is directly impacted by inflation to the fullest extent possible. There is an alternative Consumer Price Index known as the Chained Consumer Price Index for Urban Workers that does take into account consumer behavior in light of inflation pressures and was proposed by the Trump administration as a more accurate means to adjust the federal poverty level for inflation. And, as previously indicated, America vociferously said, “No, thank you.”

At this point, I hope that we have mutually arrived at the conclusion that the method for calculating the federal poverty level is outdated, inaccurate, and honestly unhelpful. The overhaul required is nothing short of throwing the proverbial baby out with the bathwater which requires a whole lot of explaining to the American public for which few have the appetite. Instead, while policymakers grumble behind-the-scenes about the rank stupidity of the federal poverty level determination regime, they tinker with the levers that are accessible to expand or constrict households’ eligibility for income-based programs and the amounts of benefits distributed.

There are three “solutions” that are continuously on someone’s agenda.

First, adjust benefit amounts. The most popular lever, it is a backdoor means of expressing skepticism regarding households’ actual neediness and the gap the government should and will cover. These calculations often try to take into account the government cash benefits that the federal poverty level does not thereby decreasing the amount households “need”. How benefit amounts are determined is a dizzying array of different data sets and calculation methods that vary widely across federal departments and the states. For example, the federal Social Security Administration uniquely uses the “controversial” Chained Consumer Price Index for Urban Workers to determine annual benefit adjustments for inflation. Bizarrely, but understandably, while the federal poverty level determines a household’s eligibility for an income-based program it is not used to calculate the benefits they will receive.

Second, adjust the eligibility guidelines. Regardless of how income-based guidelines are presented to the public, they are actually calculated as a percentage above the federal poverty level—e.g. people earning 150% above the federal poverty level and those earning at or below it are entitled to ‘X’ assistance. What politicians fiddle with is the percentage—how many gradients above the federal poverty level are we willing to provide assistance for? And while sometimes the percentage changes are ridiculously small, they will often impact thousands and tens of thousands of households. It is also important to remember that poverty is a continuum wherein being more than 150% above the poverty level (defined as not needing assistance in the example above) in no way translates to a household that is not experiencing poverty. One of the small measures of backlash against the federal poverty level calculations is that additional criteria is implemented to determine if a household demonstrates need. Yes, sometimes these additional eligibility criteria seem petty, onerous, or even mean but they are also linked, I strongly believe, to a general deep skepticism about whether the federal poverty level, as it currently exists, is an accurate indicator of need.

Third, increase the robustness of the federal poverty level by including basic costs, other than food, that households incur. The prime variable to base the federal poverty level on would be housing costs which can be as much as or more than 35% of a poor household’s budget. The problem with this proposition or any method that includes housing as a variable is that housing costs vary dramatically around the United States and unless we are prepared to do regional federal poverty levels, housing is a wild card of an indicator to rely on.

For example, the average household in our 7 midsize city sample spends $20,528 on housing. This is $10,000 less than the average Boston household and smacks of inequity.

If the federal poverty level calculation is broke, how do we fix it? I would suggest four major changes.

First, the metric needs to be more robust in terms of the variables it includes to determine a family’s basic needs. It should include, at minimum, three of the costs used in this post for our 7 midsize city sample: food, housing, and medical care. This is representative of whether or not a household is able to meet the basic needs of its members. The data for doing so is already available through the federal government and used by MIT for its living wage calculations.

Second, the metric needs to include a more realistic inflation index to avoid overstating the impact of inflation on households. The Chained Consumer Price Index, already employed by the Social Security Administration to adjust benefits for inflation annually, provides an evidence-based, rational model of consumer behavior to inform its calculations of how inflation actually impacts costs for consumers. And yes, we will need to accept that historically inflation calculated by the Chained Consumer Price Index is less than is calculated by the Consumer Price Index we are using now which might mean that fewer individuals, based on Chained Consumer Price Index inflation adjustments, will be eligible for income-based benefits.

Third, we need to confront fairness, squarely. An oft heard complaint is that the poor get so much help while the working poor do not. On the one hand, poverty is poverty and no one is getting rich off America’s barely adequate social safety net. On the other hand, there is a lot of assistance directed at low-income Americans and hence it feels like unfairness. One of the ways to restore a sense of fairness might be to include state and federal cash-based assistance as part of benefit seekers’ incomes. This would likely reduce the poor’s eligibility for receiving multiple benefits simultaneously but it would recognize the true resources at their disposal and not negate the net positive impact of taxpayer support for anti-poverty programs. Sometimes we do need to give in order to get.

Lastly, and probably most dreaded is that the federal poverty level must be regional. Poor people in Boston shouldn’t be penalized for the fact that the housing market there is a nightmare. On the flip side, the El Pasans whose cost of living is extremely low should not over-benefit from the higher median cost of basic household expenses for other similarly-sized cities.

We cannot have intelligent conversations about poverty in America if we do not have the right tools to measure it. Even more importantly, we cannot combat poverty if we do not account for the drivers of poverty—housing, food and medical care (in that order). Making the portrait even more complex is the steep cost of childcare which impacts two-fifths of all households. In Washington, DC, for example, childcare is 46% of a living wage income. While it is unlikely that childcare would ever be considered in the calculation of the federal poverty level, it should be more widely and deeply considered in determinations of benefit amounts.

“Fairness” is a term that is often deployed by conservatives and liberals alike when discussing federal and state cash benefits like TANF and SNAP. It turns out that eligibility determinations for these types of benefits are unfair to the poor whose circumstances are not accurately captured by the federal poverty line calculation and to taxpayers whose assistance is not factored in as part of a benefit seeker’s income resulting in individual households participating in multiple anti-poverty programs simultaneously. I do not object to households receiving multiple benefits but I do recognize that it is a core factor in the long-standing grudge match between the poor and their too near cousins, the working poor. And insofar as America remains stingy in its anti-poverty measures, it is not unreasonable to arrive at a re-vamped federal poverty measure that addresses the unfairness and inequity that all parties perceive in how we define poverty in America.